'Roots in the Valley,' remembering Constantia’s displaced families

Beneath Constantia’s manicured vineyards and winding lanes lies another story - of small farmers and families uprooted by force and scattered across the Cape Flats.

Before wine estates and luxury homes, coloured families tilled the valley, growing fruit, flowers, and community. Their removal under apartheid’s Group Areas Act of the 1960s erased more than homes; it buried a way of life

Decades later, the struggle for restitution and recognition continues, as descendants, like the Lesters, Solomons, and Jafthas, fight to keep their history from being erased.

Reverend Terry Lester remembers the joy of childhood playing in the river, picking acorns, and climbing the oak tree on their property along Strawberry Lane. His grandparents farmed cut flowers for the city’s markets.

His grandmother Christine, born in Genadendal in 1896, came to Cape Town as a teenager, married a white farmer, and secured their home by bidding at an auction on Strawberry Lane - borrowing money from her grandfather’s brothers to pay the deposit. The property was purchased in 1946.

In 1965, the family was relocated to Grassy Park to a wooden-and-iron house where water seeped through the floor in the heart of winter,” he recalls.

“Decades later, when a memorial plaque to Constantia’s displaced residents was proposed, developers refused it on their land, so the City placed it on what used to be ours,” Mr Lester said.

Returning as rector of Christ Church Constantia, from 2012 to 2024, marked the beginning of a deeper reckoning with restitution and its inequities.

His family received R800 000 in restitution, divided among dozens of descendants. Mr Lester said: “That had to be divided among my father’s siblings - five or six - half of whom had already died. Then their children, and their children’s children. In the end, some people got two thousand rand,” he said.

“‘If there’s one policy that has gone nowhere, it’s restitution. We haven’t found a model that gives both dignity and income,” he said

Constantia carries no visible scar of forced removals, and Mr Lester points out: “District Six is a scar you can see. In Constantia, the beauty hides everything. People talk about the lovely wine estates, but they don’t ask who planted the vines.”

“The few remaining cottages that held coloured families have been turned into commercial spaces,” he said.

“District Six still asks the question, ‘What happened to the people?’”

In Constantia, silence prevails. Many old lanes and footpaths vanished with the subdivision of farms, but for Mr Lester the memories and stories of those who once walked them still matter.

In the early 2000s, while serving as rector of Constantia, he founded the Constantia Heritage and Education Project (CHEP), a non-governmental organisation to reconnect descendants of displaced families and preserve their history.

Making Constantia’s hidden history visible is deeply personal. For Mr Lester, the question “Where do you come from?” lies at the heart of restitution.

The question is answered through the lives of families who once called this land home. Among them is Rashaad Solomon, one of the key founding members of the Solomon Family Trust.

“I was born there," he says, of the property his grandfather bought in 1902, and where Constantia Emporium stands today.”

For generations, the Solomons farmed fruit, vegetables, grapes, and flowers.

“Every week about 20,000 bunches of carrots went to market,” he recalls. “People would fetch flowers on Thursdays or Fridays to sell at the Grand Parade.”

Their land stretched across what is now prime Constantia, from Spaanschemat River Road to Ladies Mile, and later split in two by the Simon van der Stel Freeway.

“None of our uncles worked for anyone else. We worked for ourselves.” That independence ended in the 1960s when Constantia became a white area under the Group Areas Act. The family resisted until 1965. My father’s aunt was over 90,” he recalls, adding that she said ‘You can do whatever you want, but I will not move.’

She died there.

Their homes, including “a grand Victorian homestead on Ladies Mile Road and the stone cottages were bulldozed,” were bulldozed in 1976. Their family was scattered to Parkwood, Surrey Estate, and Philippi.

“When they passed the new Constitution and the Restitution Act in 1994, I filled in the papers,” he said. “They wanted to give us alternative land. I said no - we want that land.”

It was a long and costly struggle.

“It cost us over R400 000, and the process took from 1996 to 2008. The transfer only came through in 2012. But we succeeded.”

The story of Constantia’s displaced families extends to the Jaftha family, whose roots reach five generations, and carries its own legacy through the Jaftha Flower Farm. Run by brothers Charles and Malcolm Jaftha, their great-great-grandmother, Susan Williams, is remembered as “the matriarch of Strawberry Lane” - the woman who planted the strawberries that gave the road its name.

“She had seven sons,” Charles Jaftha explains. “All of them worked the land.”

According to Mr Jaftha, local families along Strawberry and Violet Lanes farmed flowers and fruit across smallholdings from Groot and Klein Constantia to Buitenverwachting.

“Our fences were rows of fruit trees or agapanthus. You could walk from one backyard to another. If fruit was in season, you could pick from your neighbour’s trees, as long as you didn’t break the branches.”

Mr Jaftha was five when his family moved to Parkwood. “We were a bit too young, but our parents buried it - and trauma is something that comes back years later.”

It hit his father, he says, before he died in 2020.

“He started talking about it at last - about my grandmother in her wheelchair being moved from her garden to a flat in Manenberg. He couldn’t bear it. Every time we spoke about Constantia, he just cried,” Charles said.

Even after the removals, the family’s link to Constantia endured. Charles’s grandfather was permitted to tend his garden until the mid-1970s; he later entrusted his dahlia bulbs to a local farmer, preserving them for sixty years.

In 1984, his father began Jaftha Flower Farm near their old home, bringing the flowers back.

Forty-two years later, Charles and his brother still farm there, carrying on the valley’s old scent, growing sweet peas, poppies, ranunculus and snapdragons.

Now, beneath the great oak tree at the flower farm, the Jafthas hope to house CHEP’s museum of Constantia’s erased community - a space to hold the stories, photographs, and memories of the families who once called these lanes home.

Haji Ismael Solomon, right and Ismail on Sillery farm, Constantia circa 1963

Image: supplied

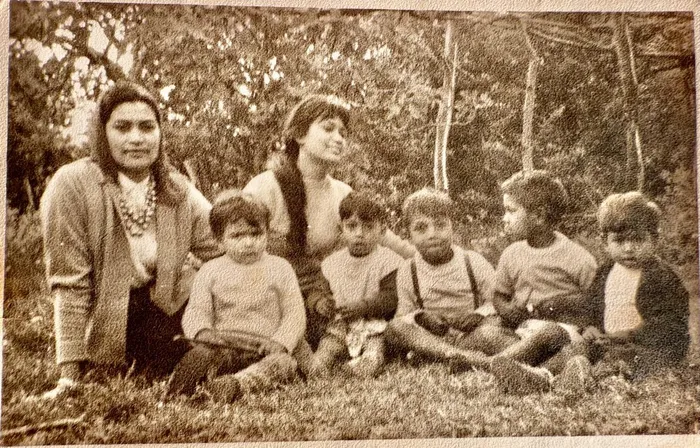

Young Solomon cousins, from left Ismail, Benyamin, Nuh, Hoosain and Abdurahman, on the farm with their aunty's Zaynub and Hajr.

Image: supplied

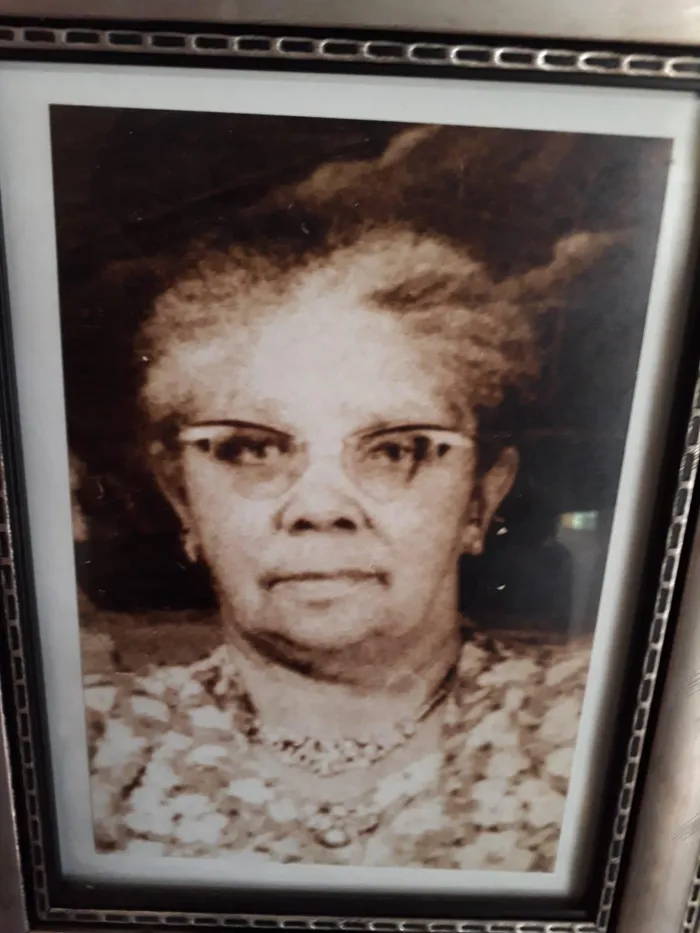

Christine Lester, originally from Genadendal, married a white Constantia farmer, and secured their home by bidding at an auction on Strawberry Lane.

Image: supplied

Reverend Terry Lester with his children, from left, Tim, Claire-Ann, Amy.

Image: supplied

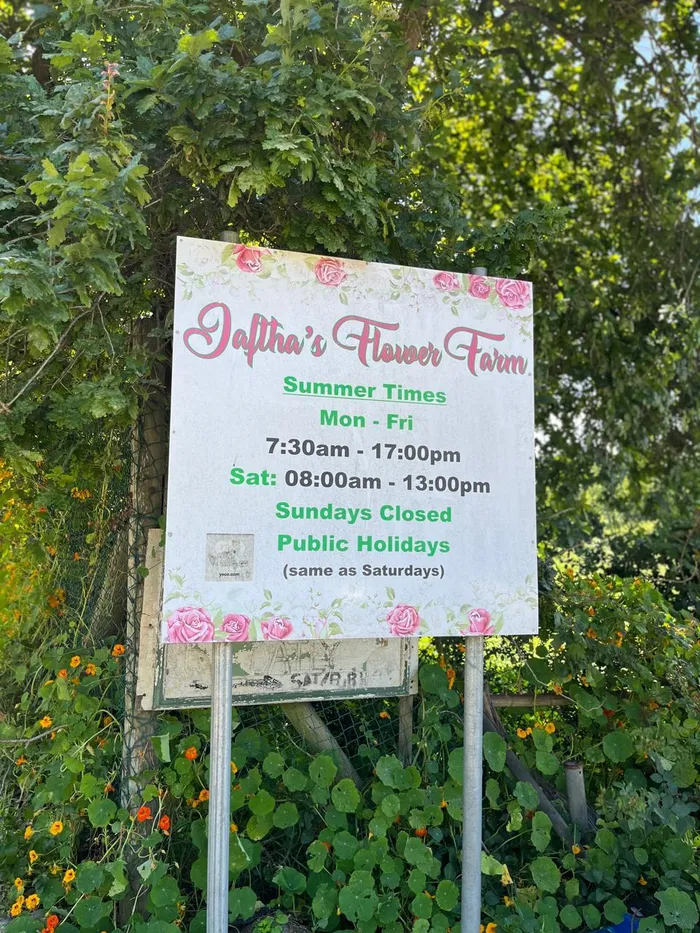

Charles and Malcolm Jaftha, following in the footstep of the forefathers who grew flowers, continue to run their family flower farm in Constantia.

Image: Janice Matthews

The Jaftha Flower Farm has been running from the same property for over 42 years.

Image: Janice Matthews

Related Topics: